I’m often asked about learning activities for various history topics and it’s something I always respond to in a similar manner, “What do you want them to learn?” Without that clear purpose as to where the activity leads the learning to, selecting the right one is somewhat harder… ok, much harder. This blog is an attempt to provide some examples of lesson activities I use and their connection to knowledge acquisition, knowledge interpretation and use/or application of skills from various subjects. It is not an exhaustive list or an exploration of sequencing activities across a unit but merely some of my favourites.

Certain key underpinnings:

The subsequent paragraphs are aspects of teaching history that need to be considered alongside activity selection… without them, history is a smattering of stuff which has a limited impact in impacting children’s understanding of the past.

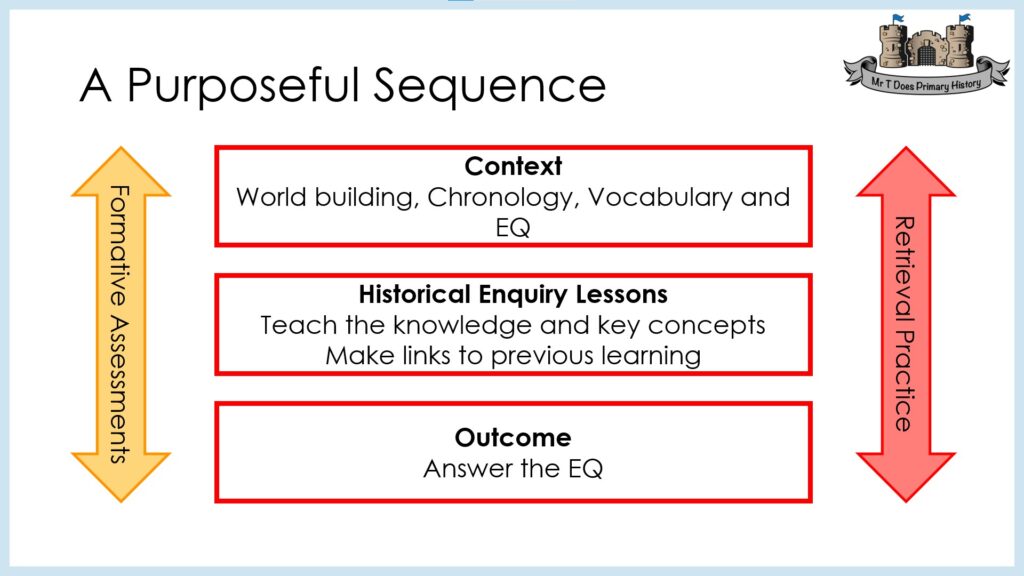

It’s important that we don’t see activities in isolation so that they offer value to a greater sense of history. To that end, my forthcoming book (this isn’t a sales pitch BUT you can buy it here…) follows a consistent model in order to support children in seeing lessons as helping them gain a better understanding of a wider narrative arc. The visual that I use is below and this blog’s focus is within what I have titled historical enquiry lessons to differentiate it from the initial context and the final answer to the enquiry question(s). Each activity adds value to the lesson’s question and therefore the overarching question.

If we aren’t careful, lessons can appear to depict isolated events or individuals. Whilst there is an element of truth to this, a more accurate idea is that attributed to Mark Twain when he allegedly said: “History doesn’t often repeat itself but it often rhymes.” This is one of the reasons that careful and deliberate retrieval practice is so powerful in order to support children in both identifying the concepts they repeatedly examine but also beginning to consider common patterns in concepts such as government, reasons for invasion and conquest etc. As such, before the activity is introduced, activating relevant memories has an important role to play. As Kate Jones writes, “Understanding of memory, such as an awareness of the limitations of working memory and harnessing the power of long-term memory, is absolutely essential for any educator.”[i] So, what am I building on and what does this add is a consideration.

Probably an obvious one but, just in case, when we break history into enquiries with questions and then enquiries into sub-questions, one activity is not going to produce the definitive answer to the question. Remember, in history our understanding is constructed using a number of sources in order to get an understanding which is evidence-led and supportable from a number of sources. The Historical Association’s Enquiry Toolkit suggests, “It is important in any enquiry to try to get pupils to use primary historical sources – e.g. things that were produced at the time. These might be documents, artefacts, buildings, pictures/paintings, film. It is also well worth checking local museums for any collections or workshops they might be able to offer. “[ii] So, think carefully about how multiple activities using a range of source material build a deeper understanding over time. Moreover, does your curriculum facilitate sufficient ‘wiggle room’ or as Emma Turner called it, the 80:20 rule of planning for 80% of the time to leave time to revisit and clarify learning.[iii]

If we don’t do anything with the knowledge, how likely is it to be transferred from the working memory into the long-term memory? As Willingham states, “Whatever you think about, that’s what you remember. Memory is the residue of thought. Once stated, this conclusion seems impossibly obvious.”[iv] As such, what will be the ‘thing’ your children think about because of the activity. Will it be that they had a lovely time making something OR what it adds to their knowledge base?

In addition, when we view history as a narrative subject (which it is!), we need to think about which parts of that ‘story’ we are choosing to emphasise hence the important role enquiry questions provide. The role of the question is to provide absolute clarity as to which part of the story is core to our understanding and which is the hinterland or background which ensures the story functions and makes sense. It’s important to consistently renew the connection between individual lessons and the wider enquiry in order to provide a consistent sense of why this knowledge matters in its own right and to the wider topic at hand… you can’t teach all of it!

Pre-requisites to the lesson:

These conditions are different as they are not unique to history and the manner in which it is taught. It combines thinking about the logistics of the classroom setup and the inevitable overlaps of children’s developing understanding of skills and knowledge from elsewhere in the curriculum.

What are the practicalities of the lesson? Now, some of my favourite lessons have been really hands on… I’m sure you know the ones! A trip, handling artefacts in the classroom, or conducting a mock archaeological dig. However, these need so much careful planning in order to gain lots from them. Connect them up with other source material and think about their role in the overall enquiry process. Alongside this, it is unrealistic for such lessons to be the mainstay of our teaching because there are 11 other subjects to consider. Also, can the activity be run in the classroom effectively? It’s important to consider the potential carnage which can erupt from a surprise ‘wow’ without sufficient expectation setting. Teacher workload is something to be taken very seriously! Do you have the capacity to run this lesson in terms of prep and the nature of the lesson being implemented in the classroom itself?

How are the children going to engage with the activities? This consideration is inevitably going to vary from classroom to classroom and year group to year group. Some key considerations to think about include:

- Activating relevant prior knowledge. Whilst I briefly mentioned retrieval before, it’s important for two regards. First, it allows children to constantly activate and then utilise knowledge from prior lessons within the unit to see how events are connected when it is relevant to connect the wider narrative. Secondly, it allows them to look further back to prior units and year groups then make connections in order to “Cumulatively, pupils’ knowledge of periods and events will form a network of knowledge that might be conceptualised as a ‘mental timeline’. This is an example of a complex schema…”.[v] This needs to be deliberately and explicitly taught so it becomes a normal part of the teaching sequence. In addition, “Progress, therefore, means knowing more (including knowing how to do more) and remembering more. When new knowledge and existing knowledge connect in pupils’ minds, this gives rise to understanding.”[vi] So it’s doubly important this is facilitated.

- What pre-requisite skills and knowledge do the children need to have to engage with the task, record observations/thoughts and discuss their findings? Children need to have a certain level of experience and fluency with an activity in so that they can both take part and learn from it. Emma Turner discusses this with reference to knowledge organisers and booklets with the key point – what do children need to have in their toolkit in order for it to be purposeful?[vii]

- Recording observations and answering questions doesn’t need to include extensive writing. In the 2023 Ofsted subject curriculum insight video for history, HMI Tim Jenner explains that extended writing is a useful endeavour and has lots of value (not an exact quote) BUT, it is not always the best way to ascertain what children know. Therefore, think carefully alongside point 2 as to whether the activity includes effective ways to discuss, record and think deeply about what knowledge they have gained. Scaffold carefully and then withdraw it as and when children are able to make a more independent role.

Finally (and sorry it took so long!) where is it going and how do you know if it has been accomplished?

Examples of activities:

Below, I’ll share some of my favourite activities when teaching and endeavour to place them within the context explained above. I have tried to show how it forms part of a wider lesson by including the introductory instruction alongside where it sits within the wider unit. Models of teaching such as the core subject mainstay of ‘I do, we do, you do’ and then included screenshots of relevant slides of activity sheets (Because of the tight turn around, I do not have the chance to use children’s actual work because of permissions, etc). Therefore, please, take the use of sheets with a pinch of salt as many can be done in books.

Narrating timelines like a story:

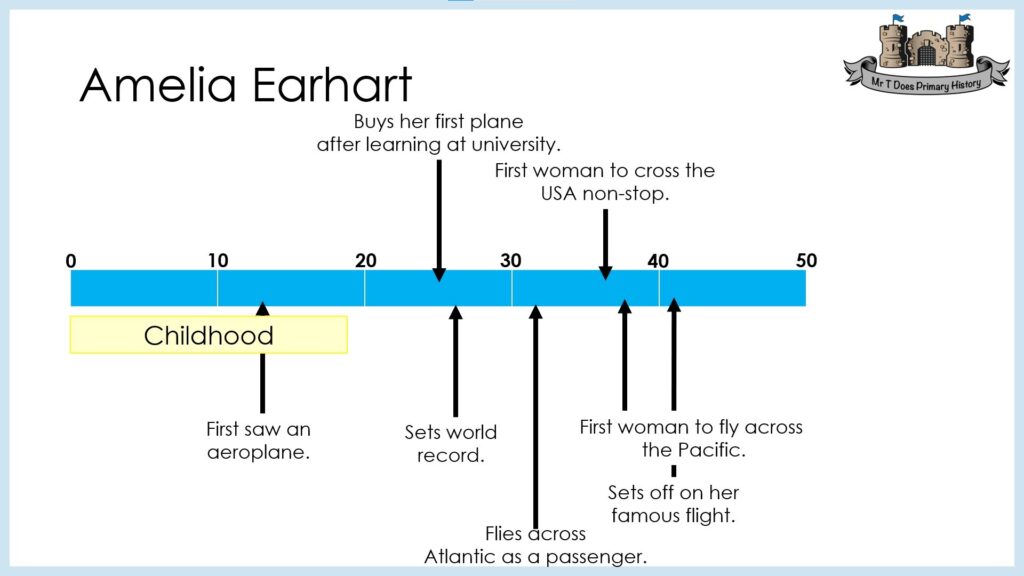

A history timeline has a similar function to a story mountain in a narrative unit of English. Reif (2008) wrote: “Poorly organised knowledge cannot be readily remembered or used. But students don’t know how to organise their knowledge effectively.”[viii] The implication here is that when thinking about the story of Amelia Earhart’s life (pictured below), we can support children’s understanding by telling the story as we might with a fictional book. After all, stories are psychologically privileged.[ix] This lesson is early in the sequence if not the initial one; its purpose is to set out the narrative children will learn more about through the unit and is a heavily guided and scaffolded lesson.

- Introduce where Amelia’s life is on the overall narrative timeline in relation to what else has been taught.

- Narrate Amelia’s life story where the teacher provides the context for vocabulary children will encounter, begins to link the timeline to the enquiry question etc. For example, she first saw an aeroplane as a teenager. This is so different to today and therefore by narrating the story, children can be introduced to why this is the case (it wasn’t invented until she was 6).

- Children interact with the timeline to build investment as to who she was, what she did and any event which, after being explored in more detail, makes them go WOW! What an achievement! Distinguish between these facts and those that are surprising in order to narrow down the field of enquiry.

- Subsequent lessons focus in on the WOW moments from her timeline and add depth to the children’s understanding. This lesson serves as an initial hook to excite them about this remarkable lady.

What goes in books? This is a question I am often asked and my initial response is… does anything have to? In an ideal world, no! Let’s keep this paced, practical and purposeful. I absolutely understand that in some schools, evidence of work in children’s books is a non-negotiable so for this lesson, I would focus on understanding and developing “botheredness” as Hywel Roberts calls it![x] So this could involve a series of freezeframes depicting the key events in her life that will be built upon in subsequent lessons or produce a cartoon strip depicting them. The end point is knowing the story to be delved into and beginning to understand her significance.

Use of videos:

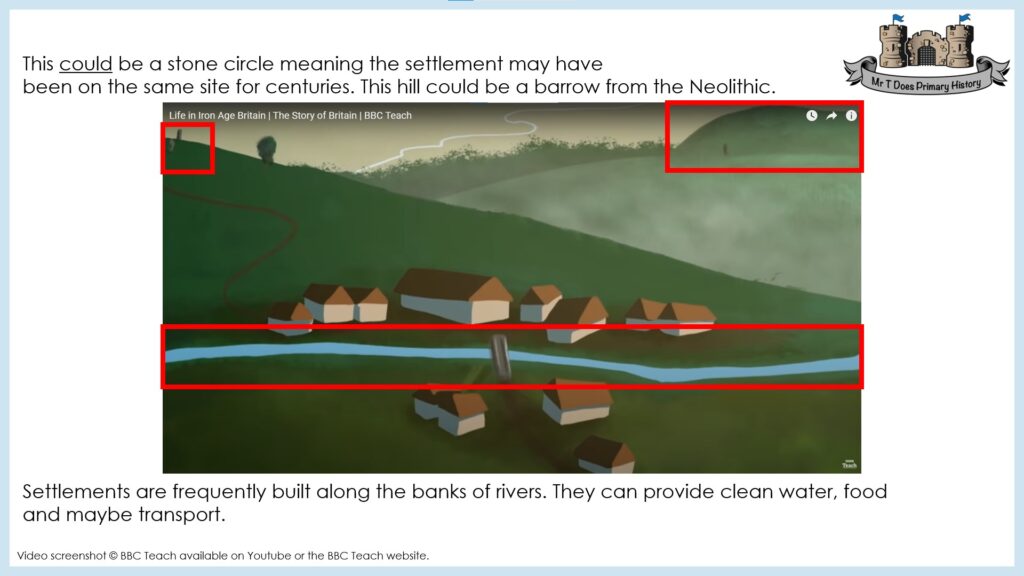

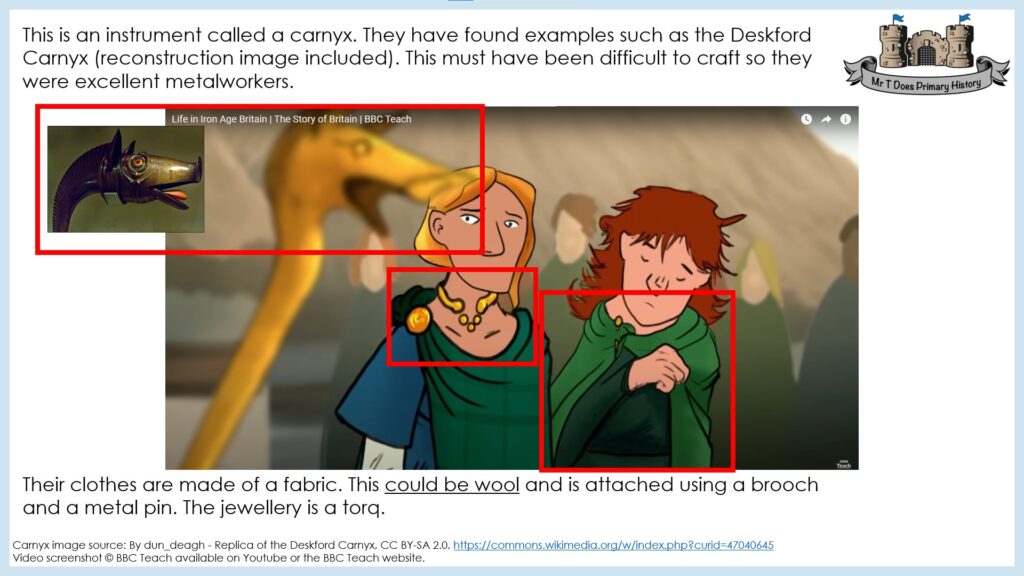

Videos are great to support children who find reading difficult (although this doesn’t mean they should never do it in history…) and can be used as a hook to captivate them within the abstract world they are delving into. I will regularly use them when teaching or planning units as an introductory way to begin to help children construct a sense of period as Dawson described it.[xi] BBC Bitesize, BBC Teach etc are great to tap into but have you used them to help connect pieces of the historical puzzle? This is when we can return to them pre and post-lesson to make connections and build a more detailed picture of the past.

- Play the video for the first time and let the children enjoy it. I’m a big advocate of moments of awe and wonder – this quite often being one of those with many cohorts…

- Then, introduce the context and purpose of the lesson. A sub-question of the overall enquiry and relate it to the timeline and maps as relevant. Re-watch the video in full or snippets as relevant and children will now watch with a sense of purpose. Using it to inform their understanding to specific historical questions.

- For the remainder of the lesson, additional sources such as books, internet sites, archaeology adds a greater breadth of understanding to what the video introduces. Use questions so as: how does this add to our understanding of x? Does this tell us something new or different? In history, we attempt to build as clear an image as possible but be mindful the children will not prove anything therefore model how to both collate answers and write conclusions.

In the children’s books, consider using snipping tool to take a screenshot of a key part of the video to annotate in relation to specific questions. Then, build a clearer picture of the past by starting with that annotated pictured and adding further images, website research (used sparingly and carefully guided!), interactives such as inspire education, Mozaik 3D and Sketchfab etc depending on what is available.

This may take more than one lesson but is a key part of the historical discipline as it ensures children in KS1 “should ask and answer questions, choosing and using parts of stories and other sources to show that they know and understand key features of events. They should understand some of the ways in which we find out about the past and identify different ways in which it is represented.” And then, in KS2, “They should regularly address and sometimes devise historically valid questions about change, cause, similarity and difference, and significance. They should construct informed responses that involve thoughtful selection and organisation of relevant historical information. They should understand how our knowledge of the past is constructed from a range of sources.”[xii] This is the bread and butter of historical enquiry so should be evident in every unit. The final example in the blog for KS1 uses a similar approach for that very reason.

Analysing testimonial sources of evidence:

Testimonial sources such as diaries, newspapers, letters etc are different to archaeology because they offer a “conscious commentary” on what they record.[xiii] As such, they need to be treated carefully and children guided through both WHAT it says but also WHO wrote it and HOW that shaped their particular world view. Without such introductory instruction, children may get a hugely over-simplified perspective of an event or have a misplaced understanding of bias (the class… which source is more reliable? Who can we trust more on this?).

This can be introduced early in Key Stage 1 when children speak to grandparents or community members about what their toys or homes were like when they were equivalent to Year 1/2 now. Oral history offers lots of relevant evidence towards the overall enquiry question but… by simply asking do we think everybody had the same childhood? We can begin the process of identifying that such sources offer a snapshot which is useful but is one of many. Then, when they encounter the Great Fire of London example below, they can activate that understanding and be supported to guide it into a new context.

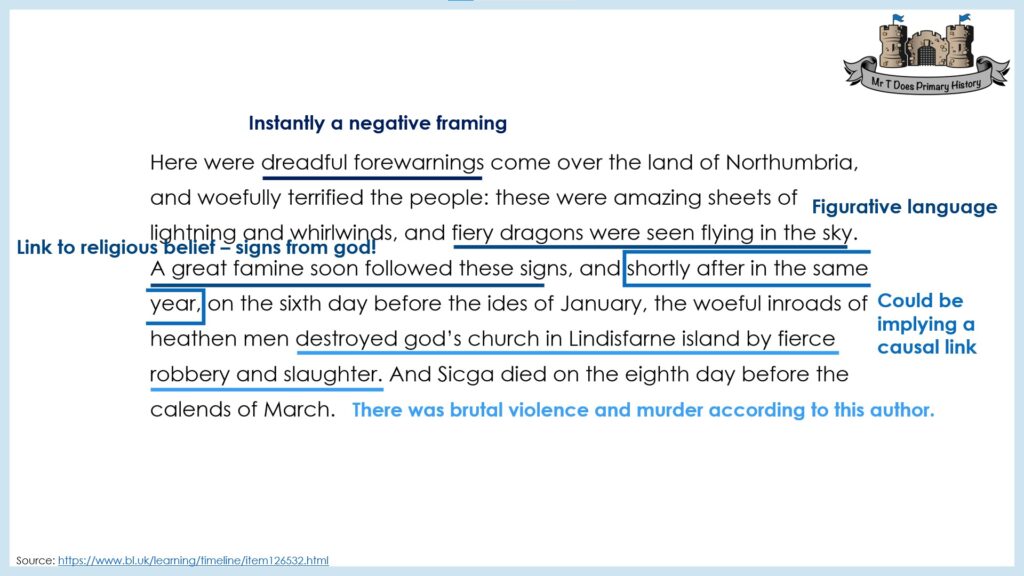

One of my favourite enquiries for KS2 challenges the perception that the Vikings were merely vicious barbarian raiders… The extract below comes from lesson 1 of the series and looking at where that perception may have arisen from at the time.

- The children are aware of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in England at this time; the fact they were NOT a singular nation and lived in small farming communities isolated from one another.

- It deliberately uses the subsequent extract of the Anglo-Saxon chronicle because it is provocative.

- Subsequent lessons which are not included challenge this perspective by highlighting other aspects of their culture such as the rich culture, trade routes and exploration.

In the children’s books, they analyse and annotate the extract of the chronicle and then add to this via subsequent discussion and teacher guided thinking towards not only WHAT it says by WHY this is said. It includes the use of language and how singular the message depicted is.

Building a clearer picture of the past by collating source material:

I deliberately placed this example last because it makes use of many of the examples above. It is a way in which many sources can be applied in order to build a clearer picture of the past than each snapshot in isolation.

Once again, it’s important that each source is contextualised in order to highlight both what it depicts but also how it was constructed (where relevant and possible).

Source 1 – The Great Fire of London: An Illustrated History of the Great Fire of 1666 by Emma Adams and James Weston Lewis

Source 2 – Painting by unknown, produced 1675

Source 3 – Samuel Pepys’ diary (available free online)

Source 1 – Story

The joy of using this story is that it is structured to tell the story of the fire in chronological order. It taps into stories being psychologically privileged and can run effectively alongside the teaching sequence. This is more challenging in Key Stage 2 where books are often longer and it is unrealistic to deliver this approach in every unit… but where it does, it’s a good one!

The story is analysed like the source A/S chronicle above to describe what it says and how the author may have found that out (a core part of the enquiry process). For the Great Fire of London, I would recommend this book: The Great Fire of London: An Illustrated History by Emma Adams and James Weston Lewis.

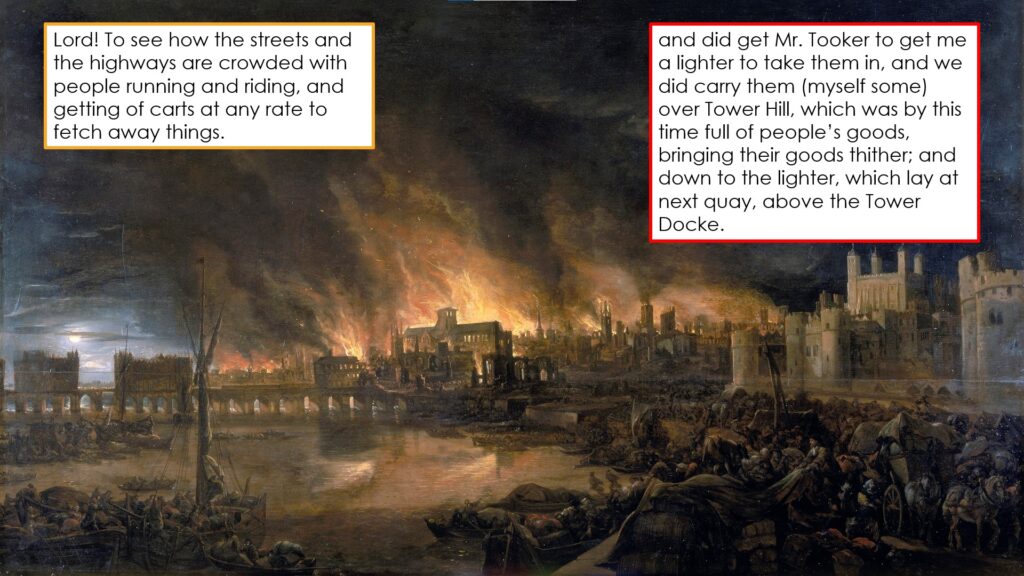

Source 2 – Painting

When looking at the painting, start by ensuring the children understand it is a valuable source of evidence because there is so much depicted within it. Looking carefully is a must and often needs to be explicitly taught. It could be broken into different frames by using a grid overlay or another approach. I tend to do this in two stages:

First, let the children look and enjoy it! What can they see happening? Listen out for children naturally linking to the story they have encountered so far and any other relevant links. If that doesn’t happen, prompt the children to make comparisons and connections. They are, after all, trying to build a firmer sense of what happened during the fire by using two sources of evidence.

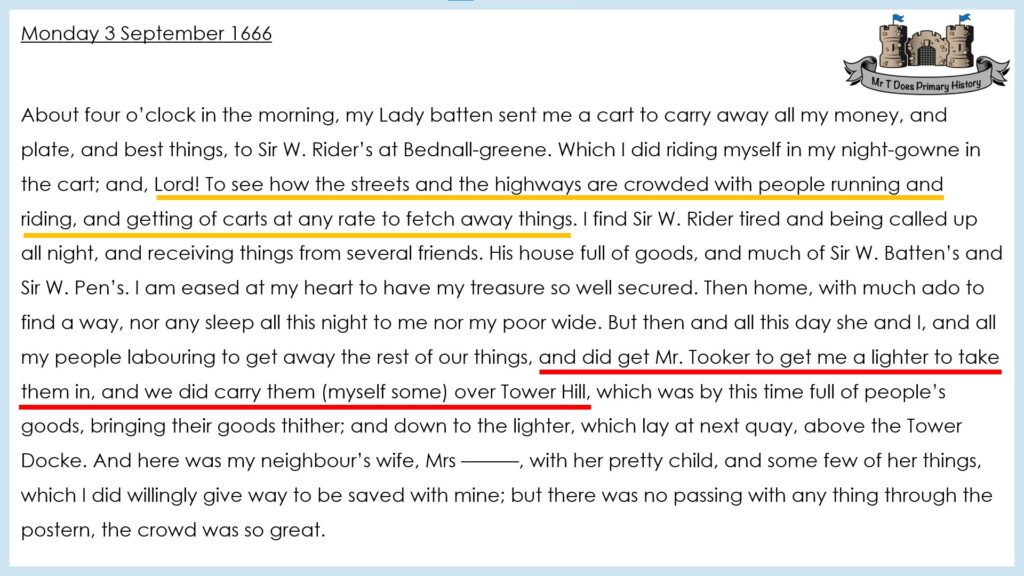

Source 3 – Pepys’ diary

Begin by contextualising Pepys’ diary in order to ensure children understand his writing is one example that we use (not the only one – John Evelyn offers another account). It is important the children know it was rare to be able to read and write in the 17th century as free education like today didn’t exist. Then, narrate extracts of the diary and create meaning (see Amelia Earhart timeline example).

Highlight that it is telling a similar story to the painting and the story book but in a different way. In the children’s books, they can annotate the source material and draw pictures or dramatise the depictions. The key is to ensure children are clear about how each source of evidence contributes to our understanding. Once we have the information, we can look across it to draw a more concrete perspective (as far as is possible anyway…).

A pinch of salt:

Every school is different and has different expectations as to what is recorded, how it is recorded etc. These suggestions are ones I make use of and can be adapted to other units. Please remember the early paragraphs as activities in isolation aren’t inherently going to add huge amounts.

I’ve endeavoured to be as clear as possible with the ideas BUT it’s easier said than done. Please do drop me an email with questions OR tell me how the ideas went for you!

Activities aren’t tasks in isolation. Make sure they add to children’s understanding and are connected to the wider narrative to be encountered. What will they learn is, and should always be, central to thinking about activities.

Relevant CPD and Resources:

I don’t write these blogs as a sales pitch so I hope it doesn’t come across that way. The ideas I have used are ones from my units of work and CPD sessions for obvious reasons. If you would like to see those sessions or resources in their entirety, you can on the links below BUT I have added the relevant context to the blog so this isn’t something you need to do (apart from the unit of work model outlined at the start).

Mr T does Primary History by Stuart Tiffany

Building a Great Unit of History

Teaching Chronology from EYFS to Year 6

Changes in Britain from the Stone Age to Iron Age Unit of Work

The Anglo-Saxon and Viking Struggle for the Kingdom of England Unit of Work

[i] Retrieval Practice: Primary A guide for primary teachers and leaders by Kate Jones, John Catt – P22

[ii] https://www.history.org.uk/primary/resource/9016/ha-enquiry-toolkit (this is free to download from the HA website… I WOULD DO THIS IF YOU HAVEN’T ALREADY!)

[iii] Emma Turner – dynamic deputies podcast – https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/emma-turner-the-interconnected-primary-curriculum/id1449384975?i=1000564994507

[iv] Why Don’t Students Like School? By Daniel Willingham, Jossey-Bass, P61

[v] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-review-series-history/research-review-series-history

[vi]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/772056/School_inspection_update_-_January_2019_Special_Edition_180119.pdf

[vii] Simplicitus: The Interconnected Primary Curriculum & Effective Subject Leadership by Emma Turner, John Catt PP73-75

[viii] Organise ideas: Thinking by Hand, Extending the Mind by Oliver Caviglioli and David Goodwin, John Cattm, P28

[ix] Why Don’t Students Like School? By Daniel Willingham, Jossey-Bass, P69

[x] Botheredness®: Stories, stance and pedagogy by Hywel Roberts, Independent Thinking Press

[xi] ‘What time does the tune start?: From thinking about “sense of period” to modelling history at Key Stage 3’. Teaching History, 135: 50–7

[xii] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239035/PRIMARY_national_curriculum_-_History.pdf

[xiii] https://www.history.org.uk/primary/resource/9931/film-whats-the-wisdom-on-evidence-and-sources